Unfolding Legacy

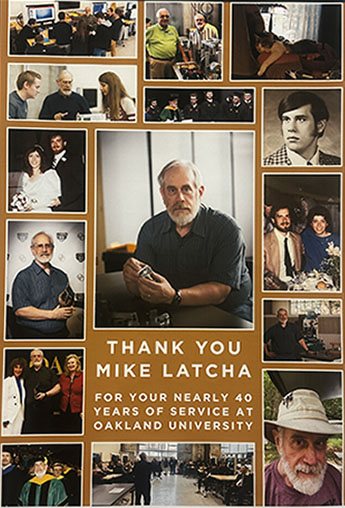

Dr. Michael Latcha retires after nearly four decades at OU, leaving a legacy defined by the lives and careers he helped inspire.

When Michael Latcha, Ph.D., professor of mechanical engineering, walks through Oakland University’s campus, he doesn’t see just buildings or lecture halls — he sees the echoes of nearly 40 years of change, growth and undeniable legacy. His eyes are lighting up with the same energy that first brought him to OU in the 1980s. However, this calling, a life-long career educating generations of new engineers, was almost missed.

Born into a family of four children, Dr. Latcha was raised with the belief that true financial security meant working for yourself. His father, an import/export coordinator, instilled this entrepreneurial spirit in his sons early on. Dr. Latcha and his older brother, Paul, initially set out to become funeral directors, enrolling in mortuary science at Wayne State University.

“In my neighborhood, funeral directors always seemed to have work,” he remembers, “and they seemed to be doing well.” But after his first year in the program and a summer learning to embalm, he discovered that this field yielded very little profit. As Paul graduated and decided to pursue a life of priesthood, Dr. Latcha thought about engineering.

He still chuckles at how casually it all began. “I went to the dean of Wayne State University’s engineering school and said, ‘If you let me apply all my first-year credits towards engineering, I’m in.’ That was it.”

After graduating in a tough economy, while many of his peers went to work for Detroit Edison, Dr. Latcha enrolled in the mechanical engineering Ph.D. program at Wayne State, simultaneously working as a teaching assistant. A few years later, married to his wife, Celest, and finishing his dissertation, he hunted for additional part-time teaching employment, just as his first child was about to be born.

“I was cold-calling universities looking for any opportunity. We had no money,” he says.

Dr. Latcha was invited to OU to give a seminar but had heard nothing for a while. Then, serendipity stepped in. After 14 hours at the hospital witnessing the birth of his son, he came home to find a large envelope from OU. Inside — a job offer.

OU was unlike anything Dr. Latcha had experienced before. Coming from the urban environment and Wayne State’s established rigid structure, OU’s wooded drive and modest student population (just 8,000 at the time) felt very different to him.

“It was literally in the middle of nowhere,” he notes, “but it was friendlier. Departments weren’t walled off from one another. People talked to each other and worked on things together. A fun story: I kept seeing these gigantic guys walking around campus. I had no idea who they were at first, so I asked around to find out that the Detroit Lions practiced here during the summer. It was really something.”

The atmosphere of experimentation and collaboration proved fertile ground for Dr. Latcha. OU’s culture struck a balance between research and teaching — a balance many institutions lacked. At larger universities, professors were pulled away from students because they were expected to chase grants. At smaller ones, the teaching load was enormous. Oakland had the balance.

|

|---|

| For Dr. Michael Latcha, nearly 40 years at Oakland University have been years of change, growth and undeniable legacy. |

In the classroom, Dr. Latcha’s philosophy was simple: meet students where they are first before taking them to the next level. Unlike professors who assumed prerequisite knowledge and plowed ahead, he took time to review fundamentals.

“Engineering is about thinking and applying ideas to novel situations, but above all, it is about safety. We’re certifying engineers who are going to create things for people to use safely. This is a big responsibility. If I’m not comfortable letting you work on my next car’s brake system, you’re not passing my class,” he shares.

That philosophy laid the foundation for what may be one of Dr. Latcha’s most lasting contributions: the creation of OU’s novel multidisciplinary Senior Design experience. The idea took shape around the year 2000, when accreditation standards changed, requiring engineering students to complete a significant design experience before graduation.

“At first, each department just went off and did its own thing,” Dr. Latcha recalls. “Everybody was building robots, but the robots were deficient because each one only tackled part of the problem. You’d have a great design with no intelligence, or intelligence with no movement.”

He saw the flaw in this fragmented approach, and the idea “to put everybody in the same room” emerged. Dr. Latcha’s vision was to create a truly multidisciplinary experience with mechanical, electrical, computer science and computer engineering students working side by side on integrated solutions. It was bold, and it was ahead of its time.

The approach sparked controversy at academic conferences. “People told us it was unsustainable. Maybe at big schools. But our size was our strength; we could be nimble,” Dr. Latcha says.

To keep the Senior Design going, Dr. Latcha ran it like a small business. He would ask companies for less than $5,000 per project — an amount small enough to receive an immediate “yes.” Over the years, that strategy proved to be remarkably effective: the program ultimately brought OU more than $300,000, $4,000 at a time. More importantly, it gave students a competitive edge.

“Industry sees the difference. Contrary to many other engineering graduates, our alumni don’t need a year to rotate across the fields to get up to speed. They can productively work in teams from day one,” Dr. Latcha adds.

Dr. Latcha’s major legacy, however, is in the lives he touched. Early on in his OU tenure, he was asked to join the faculty union bargaining team. The university’s faculty pay structure was so complex that only a few people on campus understood it. A committee was created to develop a better structure, and it needed someone who could not only understand the math but do it fast. Dr. Latcha stepped in and stayed very active in the OU-AAUP leadership until his retirement.

“I hope people will remember me for holding high academic standards,” he says, “but also for being open: to better ways of doing things, to new ideas, to understanding other people’s perspectives.” When colleagues brought him personal problems, seeking his professional advice, they frequently also found a helping hand. Service went beyond committee work. It became connection.

“And I hope people remember me for my strange sense of humor,” he smiles.

As he prepares to retire, Dr. Latcha has big plans. His hip has been replaced, and his bucket list is long. He wans to learn how to play piano, to visit every campground in Michigan, to watch the Northern Lights over Lake Superior, and one day, to see Scotland’s highlands and New Zealand’s peaks. Still, he hopes to stay connected to OU in some way.

|

|---|

As he looks forward, he remains skeptical of some directions higher education is heading. “AI — it worries me. We’re embracing it for everything. But thinking is a skill. If we outsource that, we lose something essential.”

Dr. Latcha’s message to the Oakland community is simple: “Keep looking for things that can be better — and work toward them.”

December 19, 2025

December 19, 2025

By Arina Bokas

By Arina Bokas